Steven Spielberg has been working on Lincoln for the better part of six years now, and as I viewed upon the final result I walked away with a profound feeling of “meh.” Don’t get me wrong, Lincoln is at times an incredibly powerful film, and some sequences hit the emotional chords at all the right moments, but taken as a whole Lincoln is more of a slog than a triumph.

The biggest problem is the film’s running time. Despite focusing on the last three months of the 16th president’s life, Lincoln is stll nearly three hours long. There’s an excellent two hour movie here trapped in this mess, and I longed for some scissors so I could cut out all the fat. Any time the film focuses on the passing of the 13th Amendment I was riveted, but the second Spielberg showed us bits of Lincoln’s home life I checked out completely. Sally Field and Joseph Gordon-Levitt give remarkable performances as Lincoln’s wife and son, but their story lines don’t go anywhere meaningful or interesting.

What is meaningful is the passing of the 13th Amendment, and that’s the real reason to see Lincoln. Spielberg isn’t shy about showing every facet of the legislative process, and every move taken to free the slaves is detailed here. Tony Kushner’s screenplay evokes Aaron Sorkin’s finest moments without fully stealing his schtick, and Spielberg’s direction calls to mind To Kill A Mockingbird, a film that surely influenced this one.

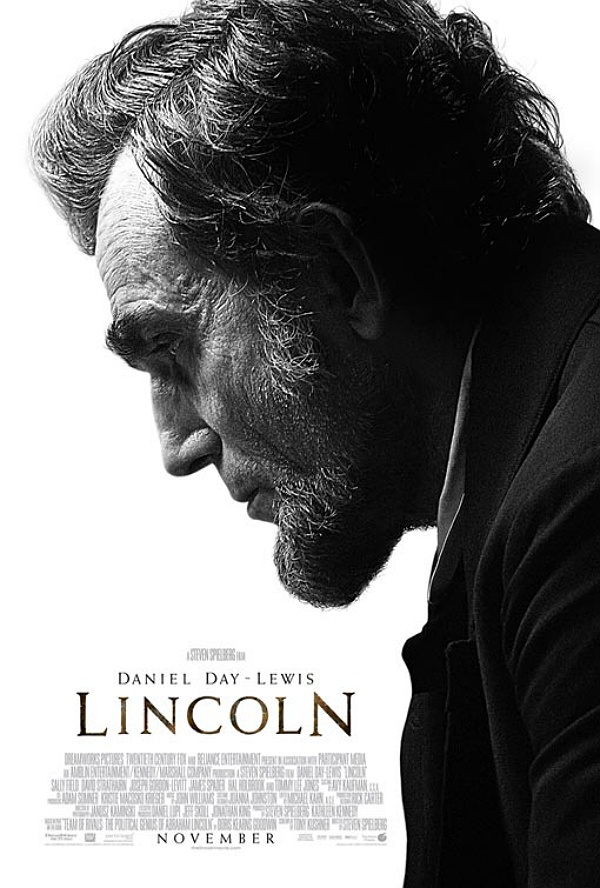

The performances here are top notch, and no review of Lincoln can squeak by and not mention Daniel Day-Lewis’ portrayal of Honest Abe. Kushner’s script fails to fully humanize Lincoln and pull him out of the god-like prism current Americans view him through, but Day-Lewis shatters that prism by completely and utterly transforming himself. This will become the definitive portrayal of Lincoln, not as a superman but as a man, a man who did an incredible thing with the help of those he could inspire not with strength or courage but words. Day-Lewis gets a handful of monologues over the course of the film, and any other actor would drown in them. Day-Lewis keeps himself afloat and still manages to play a character, fully three dimensional and real.

He’s aided by one of the finest ensemble casts in recent memory. Leading this ensemble are Tommy Lee Jones as abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens, David Strathairn as Secretary of State William Seward, and James Spader as political enforcer W.N. Bilbo. These three men are only a few of the countless perfect performances given by a who’s-who of the world’s finest actors. There’s not a single wrong note played here.

These positives only make the negatives more frustrating, and the fact is that this cast deserves a better script, one that refuses to navel gaze and moves at a strong pace. The passing of the 13th Amendment and declaration of peace was an incredibly urgent issue, and Kushner’s script doesn’t reflect that. Spielberg doesn’t help with his long takes and reliance on John Williams’ score, and another pass in the editing room wouldn’t hurt either. Lincoln is by no means a bad movie, but it simply isn’t a very good one either. At best, Lincoln is average, and my frustration with it comes from the potential to be so much more.

Lincoln is now playing in theaters everywhere.